Linguistic Fractionalization

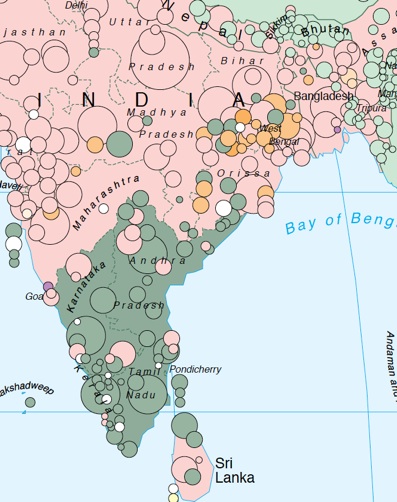

Linguistic heterogeneity: map extract India

Language families combine living languages with shared historical roots. Over time, such languages usually get differentiated to such an extent that mutual understanding is lost. By reconstructing linguistic areas, the patchwork of spoken languages gives way to a more comprehensive picture of cultural dynamic.

Looking at the Indian subcontinent, the clear-cut binary division is striking. In North and Central India, most languages belong to the Indo-Arian language family; in the South, most languages are part of the Dravidian stock. Each language family includes more than thousand spoken languages, some of them with their own writing.

A likewise split is found in Sri Lanka, too. Due to weak fedeal structures in this country, the linguistic, religious and historic differences between Singhalese („northern Indian“) and Tamil („southern Indian“) sections in the country show up as a tacid fight for supremacy and independence.

A closer look at the Indian situation reveals two more language groups in the north:

- On the one hand the Munda-speakers, mostly in Bengal and Orissa, and the Mon-Khmer speakers. Both belong to the Austro-Asian language group (orange shade), amounting to about one percent of the Indian population. Apparently, extensive interactions took place in the past between the northeast of India and Cambodian and Vietnamese areas in the past.

- On the other hand, representatives of theTibetan-Burmese language family live in the extreme Northeast (green shade). They are under strong pressure to integrate into the Indian caste system and to accept minority status in the process of steady sanscritization of the environment.

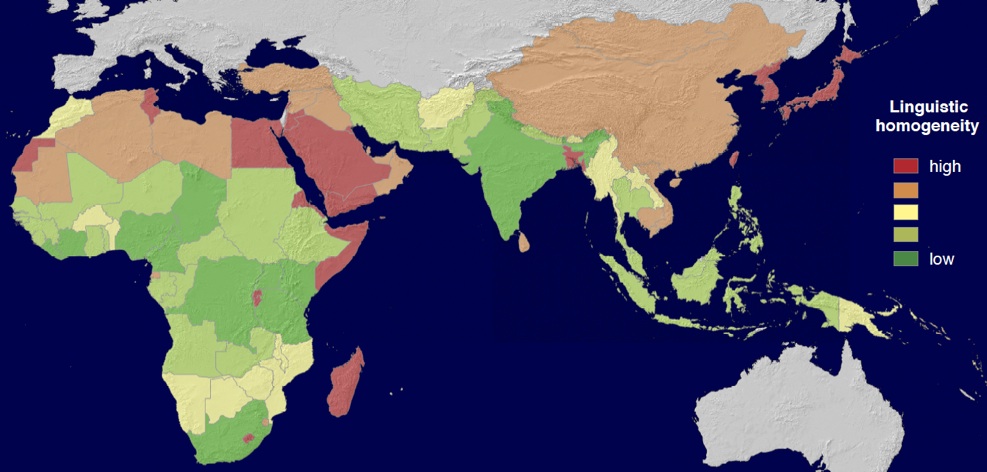

Comment on the map of linguistic homogeneity:

Map linguistic homogeneity (PDF, 3 MB)

For once, the usual split between sub-Saharan Africa (plus Melanesia) and the rest does not appear. In the light of the high political fragmentation in pre-colonial times there is little surprise that sub-Saharan Africa and Melanesia show high linguistic heterogeneity (low homogeneity: green shade). However, the same is true for India and for many countries from Iran to Indonesia – whether politically centralized or not.

More about the African situation (PDF, 96 KB)

The Arab world and East Asia, on the other hand, present high linguistic homogeneity (brown shades). Interesting exceptions are Bangladesh in Asia, Ruanda, Burundi, Lesotho, Madagascar in Africa.

Some additional hints:

- In spite of occasional deviations, the correlation between linguistic homogeneity and structural complexity is high and robust. Countries with a cultural heritage of low socio-political differentiation have no majority language group and usually show high linguistic diversity.

- The capacity to effectively deal with (ethno-)linguistic fractionalization not only depends on the vitality of democratic institutions (as mentioned in the introduction). But this very question also depends on the numeric mix of the language groups in a country. Most conflictive is a „polar“ configuration, where two or just a few large groups dominate the scene. Such examples are Afghanistan, Iraq, Fiji, Malaysia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, beside others. Under such conditions, democratic institutions are confronted with particular difficulties.

- Heterogeneous or polar linguistic configurations often appear together with other fractions running through national societies. Fractionalization usually is discussed in cultural terms: religious (e.g. Lebanon), ethnic (e.g. Cameroon), racial (e.g. Sudan). With the data of the ATLAS, another fraction line is provided to scientific research: the structural fractionalization. The term refers to countries where local societies sharply differ with respect to their traditional structural complexity – irrespective of language or religion (e.g. Vietnam, Northeast India, Madagascar, Ethiopia).