Religious Fractionalization

The essence of modern development is seen in a process of increasing complexity of the material, organizational and symbolic universe. In such perspective, development is just the contemporary form of a continuing cultural evolution. Since all institutionalized religions are interacting – formally or informally – with specific environments, any fundamental change in the environment will involve religious life as well. There is no development without transformation of religious world views. Sometimes such reorientation takes place through conversions, more often it involves dramatic reformations of time-honored belief systems.

This difference between conversion (culture-import) and reformation (culture-production) is crucial. Reformation allows for some degree of cultural continuity and self-controlled change as against clashing with the own history and identity under external pressure. It is suggested that in modernization, tribal societies with elaborate ancestor religion are more prone to crisis than societies with state institutions which were institutionalized before the colonial impact. Hence the very basic religious typology which underlies the following research:

- Local, ethnic or oral religions like ancestor religion, animism, shamanism, totemism etc.: These forms belong to stateless social systems (low Structural Complexity). During the last 3000 years or so, both, religions and social formations, of such societies got under pressure from more complex social formations with their religions and cults. As far as the less powerful societies persisted, they were suppressed, displaced and marginalized. Against European colonial impact and globalization, their repertory of resistance is very limited. As fas as religion and philosophy is concerned, they are the candidates for conversions.

- Religions of the book like Judaism, Christendom, Islam, Hindu- and Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism etc.: They represent religions of agricultural and/or trading civilizations with dominant urban centers . Written collections of the founders´ revelations are administered by priests and theologians, often full-time working in monasteries and schools. They are in charge of performing the official cults and to continuously elaborate the correct interpretation of the holy scripts. „Archaic“ religions of the book were strongly linked to political centers to whom they provided moral legitimacy. With Christendom and Islam, proselytism and an expansive, „decontextualized“ ideology entered the stage and with that the explicit objective to target all humans in the whole world.

This simple dual typology allows to address two different lines of conflict:

The first is the structural gap. It refers to the conflict between „top“ and „bottom“, i.e. between, on the one hand, societies of (relatively) high structural complexity and religions of the book, and, on the other hand, societies of low structural complexity with ethnic religions. This gap implies a constant pressure to forced integration (or marginalization) on the socio-political level, and to conversion (or marginalization) on the religious level. This explains why most religious conversions did not take place in Asia but were – and still are – significant in sub-Saharan Africa. The structural gap is not competitive, but comprises an irreversible imbalance of power.

By contrast, the second conflict is competitive: competition between religions of books. They represent comparable forms of agrarian-preindustrial moral codes on universalistic ethic fundaments. Such levels of abstractions probably were required in the process of creating multiethnic kingdoms, states and „world systems“. This quality allows for sufficient flexibility to customize specific moral codes to changing conditions while retaining abstract ideological cores and cultural identity. Therefore the religions of the book will not disappear in a foreseeable future inspite of some pressure to „conversion“ in present times, generated not by missionaries but by the globalized western education system.

Empirical clustering of nations: The last stage of traditional conversion

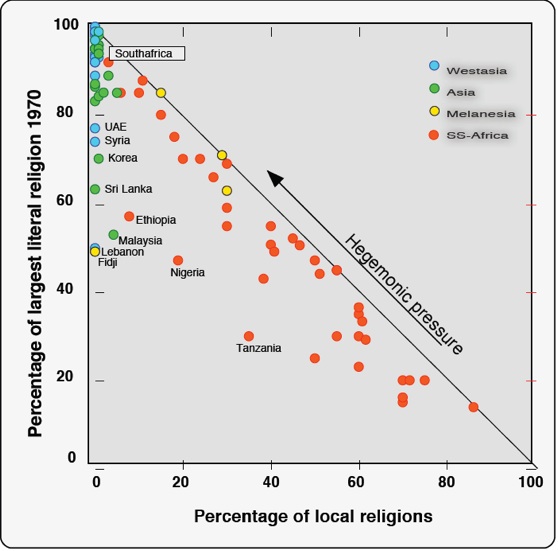

The scattergram on the left is connecting two figures: the proportion of people adhering to local (ethnic) religions (x-axis) and the proportion of the most common religion of the book (y-axis, 87 countries, values 1970).

The colors indicate that African (red) and Melanesian (yellow) countries are grouped along the „conversion line“: The total population either adheres to traditional local religions or to an imported religion of the book. By definition, local and all universal religions together are complementary values which account for 100 percent. Countries deviating from the line are those with more than one universal religion (or agnostics on the rise). African countries, more often than not, either adhere to a traditional (tribal) religion or to one, and only one, of the proselyting religions (usually christianity or islam). Often, the values of X and Y come close to 100 percent which means that a specific country gradually shifts to the camp of one of the two competing "world" religions. Till that day, they are a notorious source of social tensions since religions which are rooted in the same level of structural complexity lend themselves as vehicles for social mobilization.

The distribution visualizes the religious outcome of longterm social transformations and processes of domination: Over the course of a few thousand years, all countries moved along the line from bottom-right to top-left.

The majority of the world population now lives in countries with only one major religion of the book (on top of the figure – denominations within universal religions are not considered here). Countries deviating from the line are those with more than one universal religion (or agnostics on the rise). They are a notorious source of social tensions since religions of the same level of structural complexity lend themselves as vehicles for social mobilization.

Example of Sri Lanka: With nearly 65 % of the population, the Buddhists constitute the largest religious group. Since local religions are negligible, other religions of the book (hinduism, islam, christianity) make up for the difference. In terms of religious composition, Sri Lanka is a country with an extreme competitive pattern where all religious groups follow religions of the book (Malaysia is another one).

However, more usual and more conflictive are binary divisions with a majority belonging to only two universalistic religions – with or without ethnic minorities. While binary constellations like in Lebanon, Fiji, Ethiopia and other countries have practically no ethnic religions, Tanzania and Nigeria are examples of competitive bisection in combination with large minorities „undecided“.

The majority of the world population now lives in countries with only one major religion of the book (on top of the figure – denominations within universal religions are not considered here). The figure visualizes the religious outcome of longterm social transformations and processes of domination. At some point in the future – if globalization does not change the rules of the game –, all countries will have moved along the line from bottom-right to top-left.

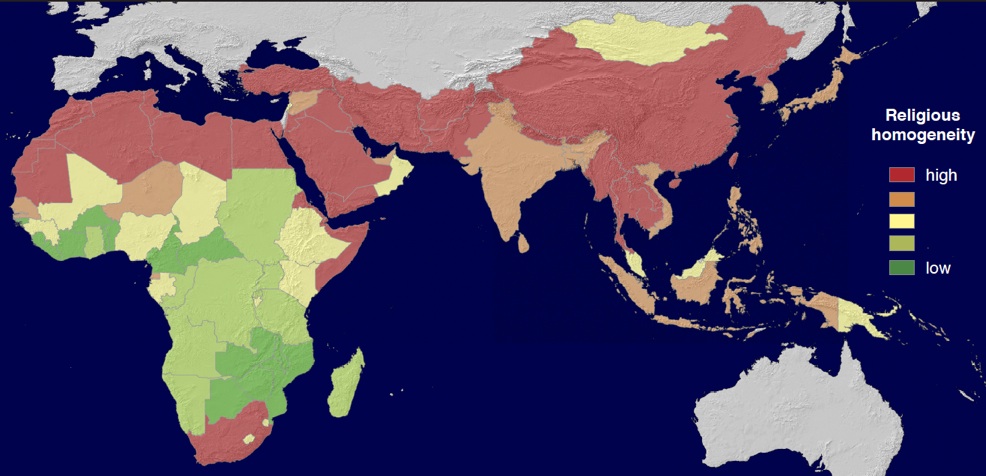

Map of religious homogeneity:

Map religious homogeneity (PDF, 3 MB)

Religious homogeneity – in terms of the largest religious group in a country - is more pronounced than linguistic homogeneity ( for Comparison). Common religion often overarches linguistically fragmented territories (e.g. in India). High religious fractionalization first of all is a phenomenon of sub-Saharan Africa and, to much lesser degree, of Melanesia and Malaysia. The relatively high religious heterogeneity in Oman and the U.A.E. results from the many immigrants from the Indian subcontinent.

As the maps of religious and (to a lesser degree) language fractionalization clearly show, the two criteria do not contribute much to understand the construction of ethnic identity. Of course, language differentiation could get enlarged when dialects are taken into accounts. And many religious denominations and sects could be considered within large religious groups.

In doing so, however, two questions arise, namely: Where are the objective limits to such differentiations? And what relevance should be attached by scientific research to such such small cultural categories?(Discussion). The relevance of cultural cleavages do not reside in the differences as such, but in the meaning attributed to them in the course of social mobilization! Therefore, we prefer criteria of cultural fragmentations which are less descriptive and more theory oriented. Examples are structural complexity and kinship systems as exposed under the main menu cultural heritage.